Artificial Intelligence and Nature’s Tenth: What is the Best Way to Regulate the Use of AI? An Expert Report on Wine Research in France

The naive use of AI is driving a deluge of unreliable, useless or wrong research. This happens, for example, when researchers report that algorithms can reliably classify images or even diagnose diseases, but fail to realize that their systems are really only regurgitating artefacts in the training data. “AI provides a tool that allows researchers to ‘play’ with the data and parameters until the results are aligned with the expectations,” says computer scientist Lior Shamir. There are checklists that can help scientists to avoid common problems, such as insufficient separation between training and test data. Many researchers are in favor of making code and data available to the public.

The only goal of the talks is to continue the style of the training data. It has and other artificial-intelligence programs are changing how scientists work. They have also rekindled debates about the limits of AI, the nature of human intelligence and how best to regulate the interaction between the two. This year is Nature’s 10 with a non-human addition.

But the technology is also dangerous. The well of scientific knowledge could be irreversibly damaged by the left unchecked automated agents. Some scientists admit to using the internet to generate articles that don’t contain confidential information.

One of the first attempts to regulate the use of artificial intelligence was agreed on by the European Union. The plan states that applications with the potential to harm people would be categorized. Some applications would be banned, such as using images from the Internet to create a facial-recognition database. The deal is provisional and legislation will not take effect until 2025 at the earliest — a long time for AI development.

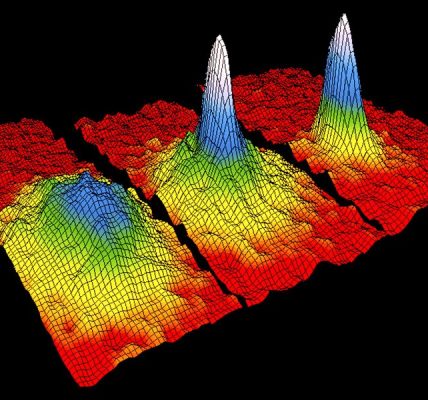

A machine-learning tool can trace the origin of wine by analysing the drink’s complex chemical profile. The formula used to find the estate on which each bottle was produced had been trained and tested on wine samples from France’s Bordeaux region. It could help the wine industry to verify their products. “There’s a lot of wine fraud around with people making up some crap in their garage, printing off labels, and selling it for thousands of dollars,” says neuroscientist and study co-author Alexandre Pouget.

Where is the women? Detecting and exploiting algorithmic bias with biomedical robots and artificial intelligence in the 21st century

Sharon Goldman, an interviewer for The New York Times, thought that millions of eye rolls would occur at once because they did not include any women. It was not noted that computer scientist Fei-Fei Li who created a huge image data set that enabled advances in computer vision was not on the list. This is “really just a glaring symptom of a larger ‘where’s the women’ problem”, Goldman writes. Isn’t we all tired of it?

Control of cockroaches by on-board computers could be used to search for earthquake survivors and sensor-carrying Jellyfish could be used to monitor climate change. Biohybrid robots such as these allow engineers to harness organisms’ natural capabilities — being able to fly or swim, for example. In comparison to machines powered by batteries, animals can stay on the move for a long time. The biggest issue with scaling up production is that most bio hybrids are handmade. “It’s arts and crafts, it’s not engineering,” says biomedical engineer Kit Parker. “You’ve got to have design tools. Otherwise, these are just party tricks.”

NatureOutlook: Robotics and artificial intelligence is an editorially independent supplement, produced with financial help from thefii institute.

Computer scientist Joy Buolamwini recalls her first encounter with algorithmic bias as a graduate student: the facial recognition software she was using for a class project failed to detect her dark skin, but worked when she put on a white Halloween mask. (NPR | 37 min listen)

What has Nature’s 10? How ChatGPT and artificial intelligence changed scientific thinking in 2023: A tale of two people and one thing

This story is part of

Nature’s 10

, an annual list compiled by Nature’s editors exploring key developments in science and the individuals who contributed to them.

Sometimes it co- wrote scientific papers. It drafted outlines for presentations, grant proposals and classes, churned out computer code, and served as a sounding board for research ideas. It also invented references, made up facts and regurgitated hate speech. Most of all, it captured people’s imaginations: by turns obedient, engaging, entertaining, even terrifying, ChatGPT took on whatever role its interlocutors desired — and some they didn’t.

Why include a computer program in a list of people who have shaped science in 2023? It is not a person, that’s for sure. Yet in many ways, this program has had a profound and wide-ranging effect on science in the past year.

For some researchers, these apps have already become invaluable lab assistants — helping to summarize or write manuscripts, polish applications and write code (see Nature 621, 672–675; 2023). ChatGPT and related software can help to brainstorm ideas, enhance scientific search engines and identify research gaps in the literature, says Marinka Zitnik, who works on AI for medical research at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts. Models trained in similar ways on scientific data could help to build AI systems that can guide research, perhaps by designing new molecules or simulating cell behaviour, Zitnik adds.

Then there are the problems of error and bias, which are baked into how generative AI works. The model of the world is built by mapping language’s interconnections, then spit back samples of the distribution with no concept of evaluating truth or falsehood. This can result in programs making up information and reproducing historical biases in their training data.

Emily Bender, a computational linguist at the University of Washington, Seattle, sees few appropriate ways to use what she terms synthetic text-extruding machines. She says that it has a large environmental impact, problematic biases and can confuse users into thinking its output comes from a person. Openai is being sued for stealing data and has been accused of exploitative labour practices by hiring workers at low wages.

The size and complexity of LLMs means that they are intrinsically ‘black boxes’, but understanding why they produce what they do is harder when their code and training materials aren’t public, as in ChatGPT’s case. The open-sourced LLM movement is growing, but so far, its models are less capable than proprietary programs.

Some countries are developing national AI-research resources to enable scientists outside large companies to build and study big generative AIs (see Nature 623, 229–230; 2023). It is not certain what level of regulation will compel developers to disclose proprietary information or build safety features.