The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness argues that social media and smartphones are to blame for mental illness

We now have two books in opposite corners that sit squarely in the middle of the fight. In The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, social psychologist and author Jonathan Haidt lays out his argument that smartphones and social media are the key driver of the decline in youth mental health seen in many countries since the early 2010s.

Of course, our current understanding is incomplete, and more research is always needed. As a psychologist who has studied children’s and adolescents’ mental health for the past 20 years and tracked their well-being and digital-technology use, I appreciate the frustration and desire for simple answers. As a parent of adolescents, I would also like to identify a simple source for the sadness and pain that this generation is reporting.

Haidt believes that a firehose of addictive content has made its way into children’s eyes and ears. The companies have changed human development on an almost unimaginable scale by replacing physical play with in-person socializing. There must be serious evidence to support such claims.

Two things need to be said after reading The Anxious Generation. The book will sell a lot of books because Jonathan Haidt is telling a scary story about children and their development that many parents are ready to believe. Second, the book’s repeated suggestion that digital technologies are rewiring our children’s brains and causing an epidemic of mental illness is not supported by science. Worse, the bold proposal that social media is to blame might distract us from effectively responding to the real causes of the current mental-health crisis in young people.

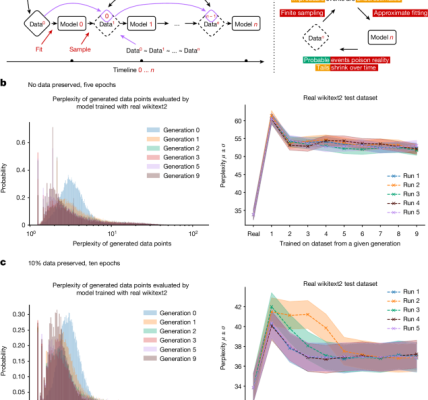

Haidt supplies graphs throughout the book showing that digital-technology use and adolescent mental-health problems are rising together. On the first day of my statistics class, I draw parallels between two phenomena and ask the students what they think is happening. Within minutes, the students usually begin telling elaborate stories about how the two phenomena are related, even describing how one could cause the other. The plots presented in this book will help my students learn the basics of causality inference and how to avoid making up stories by simply looking at trend lines.

There are no simple answers. The onset and development of mental disorders, such as anxiety and depression, are driven by a complex set of genetic and environmental factors. Suicide rates among people in most age groups have been increasing steadily for the past 20 years in the United States. Researchers cite access to guns, exposure to violence, structural discrimination and racism, sexism and sexual abuse, the opioid epidemic, economic hardship and social isolation as leading contributors8.

The current adolescents were raised during the Great Recession of 2008. Haidt suggests that the resulting deprivation cannot be a factor, because unemployment has gone down. But analyses of the differential impacts of economic shocks have shown that families in the bottom 20% of the income distribution continue to experience harm9. In the United States, close to one in six children live below the poverty line while also growing up at the time of an opioid crisis, school shootings and increasing unrest because of racial and sexual discrimination and violence.

The good news is that more young people are talking openly about their symptoms and mental-health struggles than ever before. It’s good that there are sufficient services available to address their needs. In the United States, there is, on average, one school psychologist for every 1,119 students10.

The Elephant Rides: Lessons from Haidt’s Animal-Theoretical Approach to Adversarial Research in Children’s Mental Health

In fairness, Haidt admits that he is not a specialist in clinical psychology, child development or media studies because of his work on culture and morality. In previous books, he has used the analogy of an elephant and its rider to argue how our gut reactions (the elephant) can drag along our rational minds (the rider). Subsequent research has shown how easy it is to pick out evidence to support our initial gut reactions to an issue. A lesson from Haidt’s work is that we should question assumptions that are not true. The world used to be flat. The falsification of previous assumptions by testing them against data can prevent us from being the rider dragged along by the elephant.

A third truth is that we have a generation in crisis and in desperate need of the best of what science and evidence-based solutions can offer. Our time is being spent telling stories that don’t have any basis in fact, and that do little to support young people who need more.

The evidence is equivocal on whether screen time is to blame for rising levels of teen depression and anxiety — and rising hysteria could distract us from tackling the real causes.