The South Korean campus of Ewha Woman’s University and new initiatives by the South Korean Ministry of Education: R&D funding, scholarship opportunities, and research opportunities

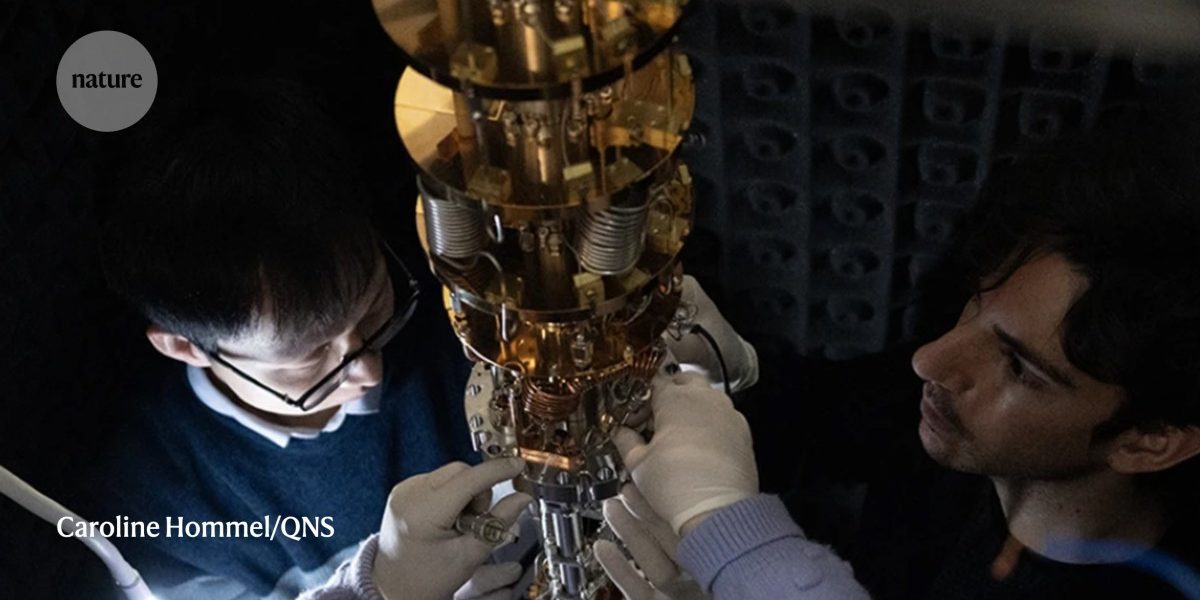

Director of operations at QNS,Michelle Randall, shows off the facilities on the campus of Ewha Womans University. “This is where we isolate our scanning tunnelling microscopes (STM) from any vibrations,” she says, pointing to an 80-tonne concrete damper, a mechanism that reduces interfering movements to near zero. Researchers at QNS are using STMs to image and manipulate individual atoms and molecules, chasing breakthroughs akin to last year’s assembly of a device made from single atoms that allows multiple qubits — the fundamental units of quantum information — to be controlled simultaneously (Y. Wang et al. Science 381, 86, and 2023). The work, done by QNS in collaboration with colleagues in Japan, Spain and the United States, could have applications in quantum computing, sensing and communication.

Randall says diversity of teams in its labs gives QNS an edge. She says that their composition is 50:50 South Korean and international, and they are an English speaking workplace. “We invest heavily in building relationships with our domestic scientific community and worldwide,” she adds, pointing to one room with four women — two South Koreans, one French, and one Iranian — exemplifying the collaborative spirit.

New initiatives by the South Korean Ministry of Education include annual financial support for master’s, PhD and postdoctoral researchers. The measures aim to give local students incentive to continue in research. To help attract 300,000 foreign students, the ministry has a project called “Study Korea 300K Project”. Students will be targeted at events and language centres abroad and science graduates may be offered an easier pathway to permanent residency and South Korean citizenship. Language proficiency requirements for admission will also be reduced. The Global Korea Scholarship invitation programme is being expanded and will increase the number of recipients from 4,100 in 2022 to 6,000 by 2027. India and Pakistan are identified as important sources of engineering talent by the ministry.

This problem has been made worse by recent policy changes. The South Korean government slashed R&D funding by 16.7% in 2023, but later rolled it back after a backlash. R&D spending remains at approximately 5% of GDP, which is far above the 2.8% OECD average, and some targeted cuts to certain programmes is probably warranted, Hemmert says. But the way the cuts were implemented to basic funding has a disproportionate impact on young researchers, says So Young Kim, because student and postdoc stipends come directly from a professor’s own funding.

The number of natural-sciences articles in the Nature Index that have been co-authored by China- and South Korea-based researchers has grown considerably in recent years, up 222% between 2015 and 2023, compared with US–South Korean output, which dropped by 4% over the same period. But South Korean researchers report that collaborations with China are becoming more difficult, particularly in technology areas. According to data from South Korea’s national police agency, of the 78 cases of industrial technology leaks recorded between 2018 and mid-2023, 51 involved leaks to places or people in China. There is now also more oversight of collaborations with China than with other major research partners. Cha said that researchers occasionally receive requests from their institutions or the government asking who is collaborating with China. “They are aware that any collaboration may be monitored, creating a sense of censorship.”

International supply chains are increasingly vulnerable, as manufacturing is more reliant than ever on them. The COvid-19 flu and the wars in Ukraine and Gaza have created challenging conditions for South Korea to grow its export-oriented economy. With the US–China trade war, South Korea is once again sandwiched between two great powers and only has one way to survive, again, by digging into its strength in technological development.

Cha highlights southeast Asia, a region that has long been of strategic and diplomatic interest to South Korea, as a place with untapped potential for joint innovation projects. “For instance, in Indonesia, there’s no governmental institution in charge of AI,” she says, which could open up the possibility of future collaborations around ethical and strategic development of AI technologies.

The lack of English used in South Korean universities is a major hurdle in the country’s drive towards internationalization. The primary language of instruction at many institutions is Korean, however the number of university courses taught in English has increased in recent years. This affects foreign researchers at all career stages because they often require help from others or full-time assistance to navigate the environment, particularly in administrative matters, says Steinegger, who can manage daily life in Korean, but needs staff to help him with paperwork.

Religious and cultural differences also pose difficulties. Muaz Razaq, a student, who left Pakistan to pursue his PhD in computer science at Kyungpook National University in Daegu, is involved in a small mosque-reconstruction project next to his university that has ignited strong opposition from segments of the local community. It seems that a lot of Muslim students across South Korea have stories about being mistreated over food choices and lack of designated space for practices such as blelution before prayers.

Attracting and Reretaining Foreign Talent in South Korea: A 2023 Study of South Korea’s Techno-Technical Innovation and Technology Disciplines

It is hoped that government-funded initiatives such as the Brain Pool programme, which gives doctoral researchers access to up to 300 million won annually for three years, and Brain Pool Plus, which offers outstanding researchers with expertise in core technology fields up to 600 million won annually for up to ten years, can help to attract and retain foreign talent. New arrivals will be provided with support programs to help settle in and build networks.

Seoul Robotics, a company that develops AI-powered software for autonomous driving and traffic management, has mandated an English-speaking work environment to attract international talent. Such a culture is unusual in South Korea; although many companies have English-speaking requirements, these are often not enforced, says Evan Thomas, business development manager at Seoul Robotics. Compared to other traditional South Korean companies, he says the ability to communicate in English without constant translation has been a significant advantage.

Thomas says cultural attitudes towards foreigners can affect long-term retention. “Many South Koreans view foreigners as temporary visitors rather than potential long-term residents, discouraging them from settling in,” he says. A 2023 survey by the Korea Institute of Public Administration, a government-sponsored research institute in Seoul, seems to back this up, reporting that less than half of the respondents say they accept foreign nationals as members of South Korean society.

Hong Bui, a student from Vietnam, accepted a postdoctoral position at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich in April, after completing her PhD at QNS. Bui cites the limited permanent career opportunities that are available to international researchers in Seoul as one of her reasons for wanting to leave, despite having a positive experience in QNS’s internationally focused environment. She says that South Korean companies value overseas experience more than domestic experience.

South Korea has an uphill battle ahead of it if it wants to regain its lead in technical innovation, but its historic ability to pivot in response to dramatic changes stand it in good stead, says Hemmert. Understanding what needs to be done and having the right leadership will help implement the change.

The country is losing steam and that is hard to ignore. In the 1980s, South Korea’s compound annual growth rate of GDP per person reached almost 12%, but had slowed to 7.2% in the 1990s, 4.8% in the 2000s and 2.4% in the 2010s. This figure has not changed since and is still below Canada and Italy. “We have been growing slower and slower, and the government is quite worried,” says So Young Kim, who was appointed to chair a presidential commission in March, to propose solutions. “The new administration has been trying to revamp policies, institutions and funding structures to regain strength in science and technology, so that we can have another Miracle on the Han River.”

It is difficult for the government to secure support for measures like providing ongoing public funding for researchers who are trying to achieve long-term goals as many people in South Korea are uncomfortable with the idea. “This is a performance-based culture, so it has been difficult for people to accept that the government should be putting money into basic science” rather than more commercial areas, he says.

Short-term funding is a major issue that stifles innovation in research whether or not work is funded. “Our funding programmes are usually very short, typically one or three years,” says So Young Kim. Mid-term performance milestones are set and a heavy emphasis is placed on measuring output in terms of top-tier journal publications and patent registrations, she adds. “If you are not successful in the current programme, there’s no way to continue your research, because new funding is based on past records.” The structure of funding forces researchers to focus on quick wins.

Hemmert says you need a more patient approach for cutting-edge research. He adds that research in Japan — where the same topic can be pursued for decades in multi-generational labs — offers an interesting point of reference. “Japanese scientists have picked up a good number of Nobel prizes, but South Korea has zero,” says Hemmert. “When I looked at the profiles of Japanese Nobel scientists, they typically worked on some specific scientific problem for decades.”

There is room for improvement despite the country’s research universities ranking high in industry–academia linkage metrics. It’s a bit chequered, even though they understand the need to collaborate more.

The government is considering other options for encouraging young people into science, such as expanding a programme that allows men to serve out their 18–21-month-long mandatory military service by continuing to work in their university labs. “The bigger challenge, I think, is not how we design these extra benefits, but how we make studying science and technology a really fulfilling experience for those who are interested in it,” says So Young Kim. She says that students and early career researchers often feel like they’re stuck in the lab, rather than learning how to conduct research which can be very unrewarding. “We need to find that intrinsic motivation for our students. Professors need to become role models, demonstrating that through this career we live a meaningful life,” says So Young Kim.