Donor Cell Injection into a Diseased Liver: Insights from a Clinical Trial on a New Treatment for End-stage Liver Disease

A volunteer has received an injection of donor cells to turn one part of their body into another. The procedure was performed in Houston on March 25 in order to participate in a clinical trial regarding the treatment for end-stage liver disease.

About 10,000 people in the United States are on the transplant list for a liver, and many will wait months or years to get one. It doesn’t include those who don’t qualify for a transplant because of other health problems.

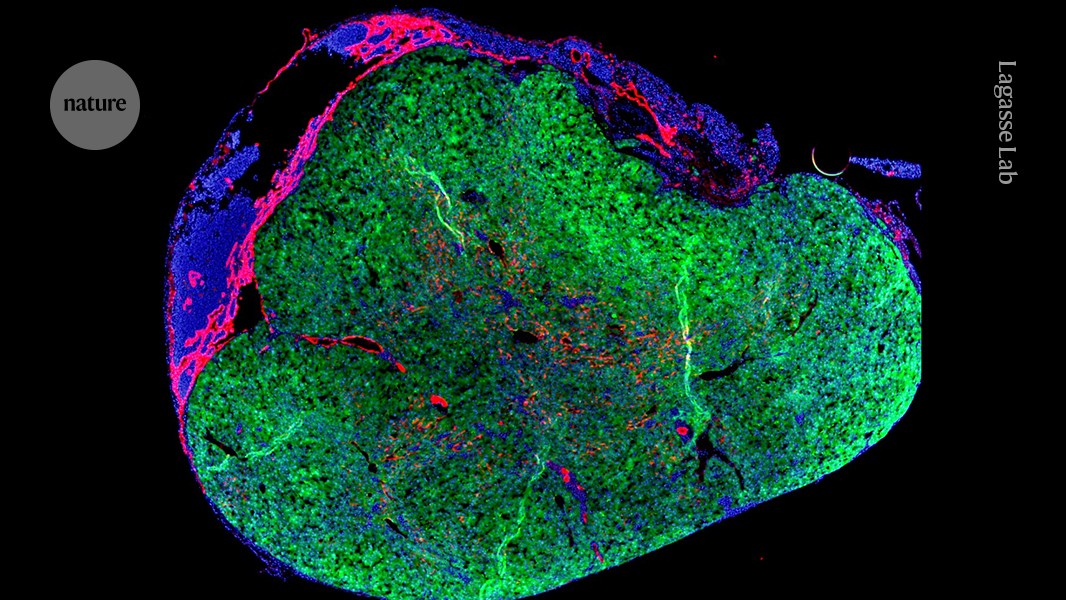

Healthy donor cells can’t be injected directly into a diseased liver because they won’t survive, says Eric Lagasse, chief scientific officer of LyGenesis and a professor of pathology at the University of Pittsburgh. There was a time when he identified thallus as a potential location for a new organ. These small, bean-shaped lumps of tissue help fight infection as part of the immune system. They also have the ability to expand and, like the liver, they filter blood. Because there are so many throughout the body—500 to 600 in adults—repurposing one shouldn’t affect how the rest do their job.

“It’s a very bold and incredibly innovative idea,” says Valerie Gouon-Evans, a liver-regeneration specialist at Boston University in Massachusetts, who is not involved with the company.

The person who received the treatment on 25 March was discharged from the clinic after recovering well from it, said Michael Hufford, the chief executive officer of the company. Stuart Forbes says that a person needs to take immunosuppressive drugs so that their body doesn’t reject the donor cells, so he isn’t affiliated with LyGenesis.

Phase II Liver Diagnosis Trial – The Impact of Mini Liver Organs on Liver Disease Survival and Quality of Liver Transplantation

More than 50,000 people in the United States die each year with liver disease. scar tissue that has accumulated during the disease can cause problems in the end stage of the illness such as preventing the organ from being able to sieve toxins out of the blood.

According to Hufford, the organs won’t grow in the lysphoid for an long time. The mini organs are dependent on chemical signals from the failingLiver to grow, if that signal is not replaced it will stop growing. It is not yet know how large the mini-livers will become in humans.

Hufford says the company plans to enroll a dozen people in the phase II trial by mid-2025 and publish results the following year. The trial, which was approved by US regulators in 2020 and will measure safety, survival time and quality of life after treatment, will also help to establish an ideal number of mini livers to stabilizing someone’s health. The clinicians running the trial will inject liver cells in up to five of a person’s lymph nodes to determine whether the extra organs can boost the procedure’s success rate.

Hufford acknowledges that the mini organs are not expected to help with portal hypertension, but the hope is that they can be used as a stopgap until a liver becomes available for transplant. These patients have no other treatment options, and it would be amazing if that could be changed.