What are the best open-source models? A research study by Dave Dingemanse and Andreas Liesenfeld at the OpenUK conference

Being labelled as open source can bring benefits. Developers can already reap public-relations rewards from presenting themselves as rigorous and transparent. And soon there will be legal implications. The EU’s AI Act, which passed this year, will exempt open-source general-purpose models, up to a certain size, from extensive transparency requirements, and commit them to lesser and as-yet-undefined obligations. “It’s fair to say the term open source will take on unprecedented legal weight in the countries governed by the EU AI Act,” says Dingemanse.

There is no clarity on how many of the models will fit the EU’s definition of open source. If you look at models released under a “free and open” licence that allow users to modify a model but say nothing about access to training data, you can see this is a reference to the act. The paper says that refining this definition will likely lead to a single pressure point being targeted by corporate lobbies.

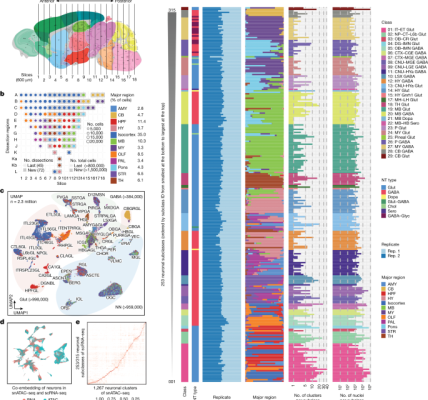

“To our surprise, it was the small players, with relatively few resources, that go the extra mile,” says Dingemanse, who together with his colleague Andreas Liesenfeld, a computational linguist, created a league table that identifies the most and least open models (see table). They published their findings in the conference proceedings of the conference.

The study cuts through “a lot of the hype and fluff around the current open-sourcing debate”, says Abeba Birhane, a cognitive scientist at Trinity College Dublin and adviser on AI accountability to Mozilla Foundation, a non-profit organization based in Mountain View, California.

OpenUK, a London-based not-for-profit company that concentrates on open technology, says this sliding-scale approach to analyse openness is useful.

Particularly worrying, say the authors, is the lack of openness about what data the models are trained on. Around half of the models that they analysed do not provide any details about data sets beyond generic descriptors, they say.

Scientific papers detailing the models are extremely rare, the pair found. Peer review is almost completely fallen out of fashion, replaced by corporate preprints that are low in detail and cherry-picked examples. Companies might have a nice looking paper on their website that looks very technical. There isn’t any specification for what data went into the system if you look over it.

And openness matters for science, says Dingemanse, because it is essential for reproducibility. He says it is hard to call it science if you can’t reproduce it. The only way to make changes to models is to have enough information to build their own versions. Not only that, but models must be open to scrutiny. I don’t know whether to be impressed by it or not, if we aren’t able to look inside to know how sausage is made. If the model is trained on many examples of the test, it could not be an achievement to pass the exam. Without data accountability, there is no one who knows if inappropriate or copyrighted data has been used.

Liesenfeld says that the pair hope to help fellow scientists to avoid “falling into the same traps we fell into”, when looking for models to use in teaching and research.

Why Finnish people don’t talk Finnish: why AI sovereignty is important to Europeans? An economic perspective from a research fellow on AI sovereignty in Finland

When a Finn talks to an AI helper like ChatGPT, they often get the sense that something is subtly wrong. “You really feel that this conversation is not the way that you would have a discussion in Finland,” says Peter Sarlin. For a start, Finnish people are known for a blunt approach to dialog and chatbots are usually tuned to be overly courteous. But there’s also the fact that most leading chatbots and the large language models behind them are developed in the US and trained on mostly US data. This is often the case with cutting-edge artificial intelligence products.

The concern isn’t just cultural, but economic. The economic value will flow to the American companies if closed source models come to dominate Europe.

The dominance of American models is driving many in Europe to talk about the concept of “AI sovereignty”: making sure that the core “digital infrastructure” behind the AI boom isn’t entirely controlled by private companies outside of the continent. Europe invests a lot in research to try to catch up with the US. But Europe’s AI challengers are starting from a long way behind. The continent lags a long way behind the US and China in the availability of capital and computing power. It doesn’t have big domestic tech companies that are vital to connecting AI products to users.

“What is sovereignty when you don’t have any champions?” says Raluca Csernatoni, a research fellow specializing in emerging technologies at Carnegie Europe, a think tank.