The Great Rewiring of Childhood: The Psychological Implications of Social Media on Mental Health and the Growing Upswing in Mental Illness

The origins of mental-health conditions can be complex and shaped by genes, family, friends and other experiences, according to researchers. The extent of that influence depends on an individual and their background, social-media platforms they use, and the content they view. Studies show that the social media response of young people varies from person to person. A 2023 review, for example, highlighted evidence that viewing self-harm content online was linked to harmful behaviour in several studies1. In some cases mental-health professionals say, troubled young people considering self- harm have found help online.

During the inquest, a representative of Meta, which owns Instagram, defended the platform’s policies, and a Pinterest representative admitted that the site was not safe when Russell used it. In response to the inquest findings, both firms pointed to ways they were improving their sites. Last year, Instagram launched ‘teen accounts’, which restrict the content young users can view.

And for some, social-media use can lead to devastating consequences. Molly Russell, 14, died from an act of self harm when she was suffering from depression and the negative effects of on-line content. The inquest was told that she had viewed self-destructive content on the platforms before taking her life.

Haidt, who works at the New York University Stern School of Business, points out in his book that the upswing in mental illness coincides with the widespread adoption by teenagers of smartphones (the iPhone was launched in 2007) and argues that this edged out real-world socializing, playing and sleep. He then draws on many studies of different types to build an argument that “This Great Rewiring of Childhood … is the single largest reason for the tidal wave of adolescent mental illness that began in the early 2010s”. There is evidence that heavy use of social media by pre-teen girls is related to anxiety and depression. “Whenever you look at anxiety, depression, you almost always find the effects are larger,” he told Nature.

Some researchers have observed potential benefits for certain groups. She says that people are using their phones in effective ways to find belonging and community, and she researches under-represented populations, which include trans and non-binary youth.

The results might help explain why some other studies find little impact, says Ine Beyens, a communications researcher who led the study. In the end, you only have a small effect when all these effects are put together.

Some researchers have criticized his views. Odgers published one of the most biting critiques in a review of Haidt’s book (see Nature 628, 29–30; 2024). His argument that digital technologies are driving an epidemic of mental illness “is not supported by science”, she wrote, suggesting that Haidt might be mistaking correlation between technology use and mental illness for causation.

The experiments where people were asked to swear off social media and phones have not been conclusive. One systematic review5 of 23 mostly randomized trials found some evidence that abstaining from social media improved measures of depression, says Ruth Plackett, a health researcher at University College London who led the review. But other studies found no effect.

It’s also unclear in some studies, say Odgers and some other researchers, which comes first: whether social media causes depression, for instance, or whether young people who are depressed are more likely to spend time on social media. “We might have the arrow pointing in the wrong direction,” Odgers says.

To make sense of conflicting literature, researchers have done dozens of reviews, examining many studies together with differing results. Many have found relatively weak associations and small effects when it comes to mental health. A 2020 analysis of more than 80 reviews found that there was a small negative association between adolescents’ use of digital technology and their psychological well-being. A 2024 literature review4 by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine “did not support the conclusion that social media causes changes in adolescent health at the population level”.

There’s a book perched near the top of The New York Times bestseller list about what’s wrong with kids today. Jonathan Haidt thinks that the Anxious Generation is a group of children and adolescents who are anxious because of the way they spend time on phones and social media. It jumped to the top of the list when it came out a year ago, and has stayed there ever since.

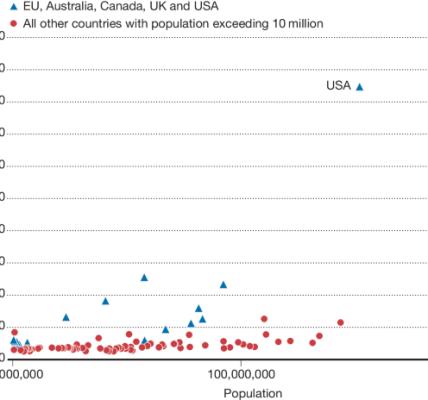

Adolescent mental health is a big concern. Research shows that, over the past two decades, rates of mental illness have been increasing in adolescents in many countries1 (see ‘Sadness epidemic’). For instance, surveys of US adolescents found that the share reporting symptoms of depression rose from 16% in 2010 to 21% in 2015 — mostly due to increases in girls — and that rates of suicide rose from 5.4 to 7 per 100,000 in the same period2. Some of these trends may be due to increased awareness and reporting of mental health concerns, but researchers have also looked for other causes.

Young people who are flourishing, resilient, power-hungry, able to balance screen time with sleep, and real-world delights must be nurtured to make informed decisions about the health of technology. Then they can then teach adults how to find that balance, too.

Finding ways to help young people navigate technology does not have to wait until its consequences are nailed down. Many schools are banning phones, giving them an ideal chance to study whether the ban improves grades and well-being. A study of 30 secondary schools in England, published in February, did not find evidence that restrictive phone policies are linked with reduced overall phone use or improved mental health4 — suggesting that phone bans might not be a panacea.

For their part, researchers should focus on well-designed, rigorous studies. They could engage in an approach used in other fields called adversarial collaboration, in which researchers with clashing views work together on shared studies that could resolve their dispute. The validity and public reception of research would be improved if more people were involved in designing it. It’s often not received well if a study says there is little negative impact, because it seems to be conflicting to what people are hearing on the ground.

The technology companies are needed to play ball in order to tease apart some parts of the tangle. Scientists want better information on how young people are using their phones. Firms that have these data are reluctant to give it to researchers. Young people can’t give research consent if they are under 18 but their privacy and security must be protected. To work out ways to access and analyse such data, there needs to be proper safeguards in place.

Some research — and common experience — suggests that phones can be distracting, and that apps can feel addictive, by encouraging people to mindlessly scroll through social-media content, for instance. Technology companies, often with business models that depend on eyeballs on screens, have an incentive to keep people hooked.