Apple’s Full-Screen Rule: A First-Principle Test of the Science and Technology of App Store Privacy and Security

The biggest decision was whether or not Apple should take a commission. Apple considered multiple options: it could take no cut but restrict where links were placed, it could charge developers based on app downloads or another metric, or it could determine a new commission for web purchases and audit developers based on their sales.

After the injunction came down, Apple began sizing up what changes it could implement that would “limit the ruling,” as one set of internal meeting notes say.

Apple had made choices to limit the text that developers could use on links. The new web and link rules were not allowed to be used by developers with reduced commission rates. It prevented developers from using dynamic links that would keep users logged in, because the company wanted to create more friction.

Designers then went about mocking up what happens when the link is tapped. A full-screen warning could be displayed if there was a small pop-up warning users that they were about to open their web browser.

The goal of Apple’s full-screen option was to get users to stop using the web. Employees discussed using scary language to warn people off after the pop up contained a paragraph of text.

An employee at Apple was instructed to add the phrase “external website” to their screen by a user experience writing manager because it sounded scary. An employee suggested how to make the screen worse by using a developer’s name instead of the app name. Another Apple employee said, “ooh – keep going.”

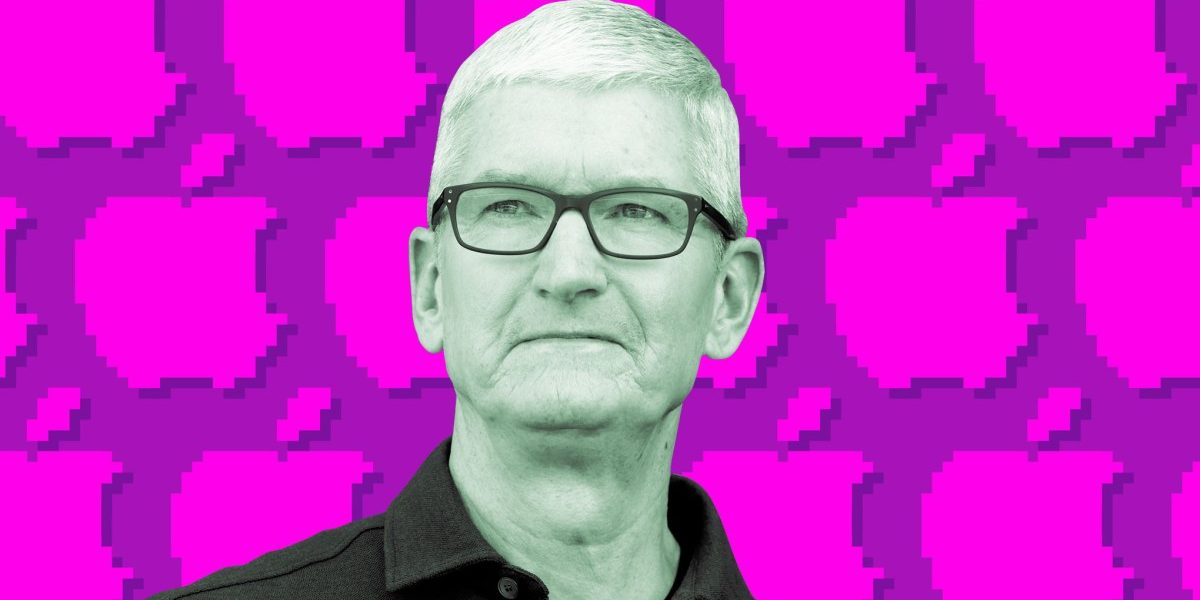

Even Cook got in on the action. When he saw the screen for approval, he asked for a warning to be added that Apple would no longer make privacy and security promises on the web.

Apple tried to convince a court that it wanted the screen to scare people and not mean it. “Scary,” it claimed, was actually a “term of art” — an industry term with a specialized meaning. In fact, the company claimed, “scary” It meant “raising awareness and caution.” The court disagreed with the argument and said it strained common sense.

Gonzalez Rogers decided Apple didn’t care about complying with her order because the company chose the worst option for developers. She wrote that Apple wanted its illegal revenue stream to be secured from every angle. The ruling says Apple’s CEO was given the option between obeying the order or paying an unjust App Store fee. “Cook chose poorly.”

Apple won the most of the legal case against it. The anti-steering injunction came about when the company walked away from the trial and the court order mandating links and buttons within their apps that would direct users to buy methods outside of the App Store. Apple’s ability to prevail in court might be a reflection of how well it did: the injunction did not tell the company what they could or couldn’t do and left a loophole that enabled them to charge developers a fee even when the product is made over the internet.

It is time for more monopoly talk after that. The companies are still fighting to keep their businesses intact. We learned a lot about how important TikTok has become, how Meta sees the world in general, and how worried it is about what might happen if there was a purchase of WhatsApp. At the District Courthouse in DC, in front of the jury, the leader of the company that’s in charge of search made a passionate case that this trial could be the end of the company.

On this episode of The Vergecast, we talk about what just happened and why it matters. After some very important party speaker updates, Nilay, David, and The Verge’s Jake Kastrenakes walk through Apple’s years of closed-door meetings about app commissions, and the ways in which Gonzalez Rogers found she’d been misled throughout the process. Nilay has taken a victory lap onbuttons and links. We discuss new things that can be bought in the App Store, which new apps may suddenly be possible, and whether Apple has any moves left in this case.